1678Mill Hill Colonial Era

1678Mill Hill Colonial EraThe name “Mill Hill” refers to central New Jersey’s first industrial site, a grist mill, erected in 1679, at the southeast corner of the present Broad Street crossing of the Assunpink Creek. Mill Hill and its wooden mill were among the holdings of the first settler in the vicinity of Trenton, Mahlon Stacy, who arrived in North America at Burlington, New Jersey on the SHIELD in 1678.

- 1999

1714Trent Town

1714Trent TownIn 1714, Mill Hill, along with much of the rest of Stacy’s holdings and adjacent lands, was purchased by William Trent of Philadelphia. The major eighteenth century development of “Trent Town” took place north of the creek, just below the “Falls of the Delaware”. This is where the Delaware changes from an estuary (a tidal body, mixing fresh and salt water) to a purely freshwater stream. This was the limit of navigation for commercial sailing ships.

- 1999

1776The Battles of Trenton

1776The Battles of TrentonWashington “crossed the Delaware” to engage in the so-called “First Battle of Trenton” in the early morning hours of Christmas, 1776. He split his force into two columns, one attacking from the west down what is now State Street, the other from the north. American artillery set up on the hill where the Battle Monument is now located. Advancing in a howling blizzard, the Continental army achieved near complete tactical surprise, and succeeded in routing the Hessian garrison. The last holdouts of the Hessian defense surrendered in what is now Mill Hill Park.

Following this success, Washington withdrew to Pennsylvania. During the following week British troops from New York were sent to Central New Jersey under the command of Lord Cornwallis. Fearing the loss of his army without another victory to boost morale (many of his soldiers’ enlistments expired on December 31), Washington again crossed to the New Jersey side of the Delaware to confront Cornwallis.

This was an extraordinarily risky maneuver, as the ice floes on the Delaware would have prevented an American retreat to the safety of Pennsylvania if the American army were to lose the engagement. Washington was betting the survival of his army on this single confrontation.

On the night of January 1, he met with his generals at the Douglass House which now stands within the district at the southwest corner of Montgomery and Front Streets. With the British approaching from Princeton, Washington decided to establish a strong defensive position along the high ground on the opposite (south) bank of the Assunpink, in a line stretching from the Delaware approximately a mile up the creek.

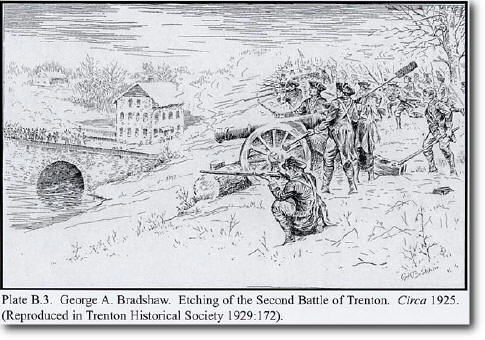

The center of the American position was the only bridge across the Assunpink, at what is now called Broad Street. Washington covered this with his artillery and his best troops, arrayed along where Mill Hill’s Jackson Street now ends.

Washington also decided to send out skirmishers to harry the British advance, along the Princeton Road (currently 206). On January 2, these detachments fought a series of actions along the route and succeeded in delaying the British advance by many hours.

Cornwallis’ army arrived in Trenton near dusk. The British repeatedly assaulted the bridge and were repulsed. With nightfall, the British suspended their attacks. Given the superior force of the British Army, there is little doubt that it would destroy the Continental Army when hostilities resumed in the morning.

However, in what is widely regarded as the single most important turning point of the war, Washington eluded them. He ordered campfires built up and maintained throughout the night by a rear guard while the main body slipped away by a back road towards Princeton.

Washington’s army surprised the British rear guard on the morning of January 3, and the Americans were victorious (the “Battle of Princeton”). Having managed to elude the British, Washington encamped his army in the mountains around Middlebrook, from which position he was able to control British movements across central New Jersey.

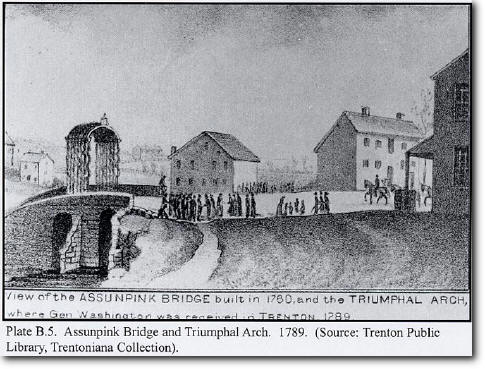

The historic nature of this battle site was recognized by the citizens of Trenton at an early date. On April 21, 1789, when Washington passed through on the way to New York City for his inauguration, he was greeted at a triumphal arch erected on the bridge over the Assunpink, by a bevy of little girls and young ladies bearing baskets of flowers. Portions of the arch are presently preserved in the Old Barracks and the Trenton Free Public Library.

- 1999

1821Mill Hill Neighborhood Established

1821Mill Hill Neighborhood EstablishedDuring the first decades of the nineteenth century, Mill Hill remained relatively undeveloped. At this time, it was not yet a part of the City of Trenton. Variously known as Littleworth, Kingsbury, and Kensington Hill, it was generally thought of as part of a section called Bloomsbury. In 1840, the entire area was incorporated as South Trenton. It was annexed to the City of Trenton in 1851.

The name Mill Hill was applied to the area at least as early as 1821, although as yet relatively little beyond the original mill appears to have been built between Broad Street and the Delaware and Raritan Canal. However, a few streets had been laid out, notably Market Street, Livingston Street, Jackson Street from Market to the Assunpink Creek, and what is now Davis Alley behind the properties on Broad Street.

In the late 1830s and 1840s, the opening of the Delaware and Raritan Canal and the Camden and Arnboy and Philadelphia Railroads, providing transportation to both New York and Philadelphia triggered industrial development on the periphery of the district.

- 1999

1836Development around the Assunpink

1836Development around the AssunpinkBy 1849 there were a rope walk, a lime kiln, and factories manufacturing fire brick and candles. By this time the original Stacy grist mill had been rebuilt as a paper mill, and an amusement park called Washington Retreat had been opened north of the mill along the Assunpink. Owned by Andrew Quintin, it featured a bowling alley, rifle gallery, soda fountain and baths.

Mill Hill grew rapidly as a residential area through the second half of the nineteenth century, with some decline towards the end of the century. City directories for the period list the following number of households: 1854, 128; 1865, 267; 1875, 194; 1885, 259; 1895, 181. The directories also reveal a good deal about the social composition of Mill Hill. Quite clearly, it was a middle class neighborhood. The population was predominantly made up of small tradesmen and skilled industrial workers, with a smattering of professionals. The numbers are fleshed out by information about the activities of some of the men who lived in Mill Hill.

Most of the buildings on Mercer Street, with the exception of the Friends Meeting House, were erected in the last three decades of the nineteenth century. Judge George W. McPherson recalled, “My father moved with his family from Front Street to Mercer Street in the winter of 1864. Mercer Street at that time was not fully built up. The only house from the Creek to Market Street on the east side was a row of four or five houses…”

The growth of Mill Hill required an improved road system. New bridges were erected over the Assunpink. A stone bridge, built between 1836 and 1849, connected Montgomery and Mercer Streets. This was surmounted by ornamental cast-iron railings in 1873. The Jackson Street crossing was spanned by a Pratt truss bridge, constructed by the New Jersey Steel and Iron Co. in 1888. In the 1850s sidewalks were required on Jackson, Mercer and Livingston Streets, and a vitrified brick pavement was laid on Jackson Street in the 1890s.

- 1999

1900Early 20th Century

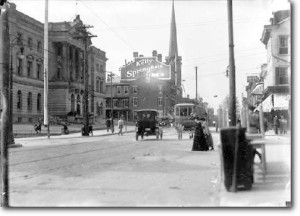

1900Early 20th CenturyIn the early 20th Century, Trenton was the economic, social, and political center of west-central New Jersey. Princeton was a small college town. Lawrence, Hamilton, Ewing, and surrounding suburbs were largely agrarian.

Trenton was an industrial center of international importance. The Roebling Steel works was in full swing, spinning the wire rope used to construct most of the major suspension bridges erected in the US, including the Golden Gate and George Washington Bridges. Trenton was also the principal centre of the pottery and ceramic industry in the United States, turning out products ranging from ceramic insulators to bathroom fixtures, to fine china.

Waves of immigrants settled in Trenton, and in the Mill Hill. By the 1920 census, 52% of the city’s population were foreign born or were born in the US to foreign-born parents. Approximately 12,000 (10%) were Jewish, and many had settled in Mill Hill. It remained a significant Jewish neighborhood until well into the 1940s, when many Jews began moving out to the western wards.

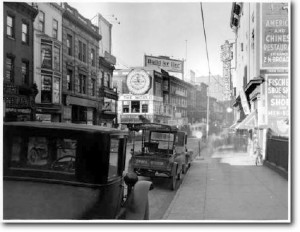

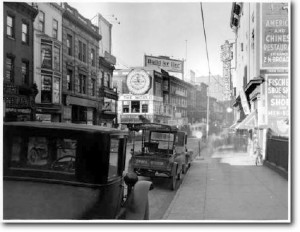

The Labor Lyceum building on Mercer Street was built by the “Arbeiter Ring”, a Jewish fraternal organization that was active in the labor movement, built in 1916. Their “AR” logo is still preserved in the marquee above the entrance and in the facade.Broad Street was a fashionable shopping strip for Mercer County, with exclusive men's and women’s clothing stores.

- 1999

1920The Great Depression

1920The Great DepressionAfter the 1920s, and throughout the great depression, many Trenton manufacturing plants were purchased by out of town owners, as part of a national trend towards consolidation. This began the economic decline of Trenton, which was slowed by WWII and the post-war boom economies. Roebling Steel was one of the last of the great Trenton enterprises to be sold, in 1953, to the Colorado Fuel and Iron Co.

Slowly but surely in the post-WWII economy, American manufacturing in the NE US declined. New investment went out of town, often to low wage, non-unionized states; and most manufacturing ultimately moved overseas. With national policies that favored the development of suburbs over center-cities, Trenton’s role as the social and retail center of the area also declined. Nationally, the “shopping mall” replaced “main street” as the predominant setting for retailing and entertainment, and Trenton suffered along with virtually every other center city in the NE US.

- 1999

1950The Decline of Old Mill Hill

1950The Decline of Old Mill HillGiven the economic decline of Trenton (which was experienced by virtually every industrial city in the northern U.S. during the period), and America’s love affair with the suburban lifestyle, the decline of Mill Hill in the 1950s through the 1970s was inevitable.

It was made worse by some woeful urban planning decisions to build roads and parking lots that destroyed large swathes of Trenton’s historic urban fabric (e.g.the Trenton Freeway, surface lots for state workers), cut off access to the Delaware (Rt 29), and much more. Here, Trenton’s position as state capital worked against it, making money for misguided urban renewal schemes readily available.

Mill Hill transformed from a predominantly single-family, owner-occupied community, to a majority multi-family, renter population. Vacant properties increased from 3% in 1952 to 17% in 1970.

The turn-around began in the mid-1960s. The City of Trenton adopted a redevelopment plan based on the idea of converting Mill Hill into a latter-day “Georgetown”. Instead of clearing and building new, the current historic fabric would be preserved. This established the basic framework that has supported Mill Hill’s Renaissance to this day.

In a symbolic act that ended up carrying enormous practical significance, Trenton’s Mayor Arthur J. Holland moved with his family to 138 Mercer Street, on February 28, 1964. This event was covered at the time on the front page of the NY Times, and in Life, Time, and Ebony Magazines. Holland paid $6,750 for his house and invested an additional $15,000-20,000 in renovations.

Derided by some as a desperate political stunt, Holland lived in Mill Hill until 1987, when he sold the house for $90,000 and moved to Hiltonia.- 1999

1960The Restoration of Mill Hill

1960The Restoration of Mill HillRestoration of Mill Hill proceeded in waves. Initial restoration focused on the 100 blocks of Mercer and Jackson, and South Montgomery. At first, real estate prices appreciated slowly. A core of original “urban homesteading” pioneers still live in Mill Hill who acquired their homes during this period, and lived in them while restoring them painstakingly, room by room. By 1967, the first Holiday House Tour took place. This became an annual event in the neighborhood: a major social event, a fundraiser for the OMHS, and an effective way to promote the neighborhood.

Prices appreciated rapidly during the real-estate boom of the 1980s. It was during this period that the Colony was built on the corner of Market and Mercer. In 1986, Passage Theatre took up residence in the Mill Hill Playhouse, which had been restored by the City of Trenton during the mid 1970s in the historic structure, a former Lutheran Church destroyed by fire.

When the real-estate bubble of the late 1980s collapsed into the savings and loan scandal, prices in Mill Hill collapsed as well.

Then a new second wave of urban pioneers began to trickle in, attracted by the lovely architecture and the well-organized, diverse community. For the first time, commercial developers, led by Atlantis Historic Properties, took up the challenge of restoring vacant structures, principally on the 200 blocks of Jackson, Mercer, and Clay. Property values increased rapidly again, starting in the mid-1990s, and have remained strong even as the real estate bubble of the new millennium has worked through a readjustment.

Today, only a handful of vacant properties remain in Mill Hill. Renovated historic structures, and historically sensitive new construction stand side by side. The neighborhood combines an exciting mix of long-time residents and new arrivals of diverse races, orientations, and professions.

- 1999

History Of

Mill HillLatest Posts

- September 26, 2023

- 1 Min Read

- May 17, 2023

- 2 Min Read

- November 22, 2022

- 1 Min Read

- November 3, 2021

- 2 Min Read

Social Media Links

This error message is only visible to WordPress admins

Error: No feed found.

Please go to the Instagram Feed settings page to create a feed.